After the Deluge

After the Deluge by Kara Walker at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

I have always appreciated Kara Walker's work, but have never really

liked it very much. She is good at what she does, but her work is overly graphic for my taste, and depends too much on too few formal elements. And it doesn't surprise me. For all its shock value, it tells the same stories over and over again. It's easy not to look at it very hard. So I was pleasantly surprised by

After the Deluge, an exhibit curated by Walker that consists of her own work paired with selections from the Met's collection. The exhibit, inspired by Hurricane Katrina, is a visual treat that gave me a whole new appreciation for Walker. She is a powerhouse! It is satisfying to compare her work to historical masters of the silhouette like Auguste Edouart, and indulge in the way she manipulates a rich set of conventions that govern precisely

how gentility and savagery are flattened into cutout representations. It is also a delight to watch her play as a curator, and I mean that in the richest, most intense sense. Love Walker's work or hate it--it is apparent that she is always having a really good time. Her maniacal close eye and strong hand are everywhere here, assembling an essay in objects and pictures that presents no new stories, but thickens old ones. In this context, it became clear that much of Walker's work was lost on me. Cutouts are, by their nature, thin and flat. Walker depends on the way she references other worlds: this rich antebellum history and a contemporary culture that is still infected by it. The knowledge, assumptions, stereotypes and experiences viewers bring to her work are what breathe life and dimensionality into it. I really enjoyed having Walker do some of that heavy lifting for me. I left the Met excited about Walker's prowess and ready to engage in a conversation with her.

And all week long I have been staring at a blank screen, thwarted and thwarted again.

Walker is masterful on so many levels, and I have been struggling with this power because much of it is gained through that systemic dishonesty pervading all discussion of race. Frankly, it's made for a frustrating week. I am eager to engage with anyone who has the technical skill and grace to whip around all this madness and badness and make my eyes drink it up. And I am deeply grateful that she has the balls to play with race within the mostly white art establishment. I love that she is not just recording racism in a didactic Adrian Piper kind of way. She is focusing all her playfulness and perversity on the single most destructive aspect of racism--the too-tight grip on slavery's legacy that wedges itself between white and black people, a constant unspoken rift that makes progress and healing impossible. And so here we are, Kara Walker and I, a black woman and a white woman wrestling in the muck.

Walker constructs the history of slavery and its constant, nagging present tense in terms of inside and outside space. She starts with the black subject as a container for what she terms "pathologies of the past," and then moves outward as this container overflows to create a muddy, treacherous social landscape infected by this degrading past. This sense of inside-outside is severely flattened in her own work, reduced to positive and negative space. She often winds up talking about a container when what she gives us is a flat black shape. This time, she gives us the whole container by pairing her own work with lots of juicy bits from the Met's collection. The black subject here is exoticized in Edouart's

South Sea Islanders, backgrounded in Copley's

Watson And The Shark, alienated in Winslow Homer's

The Gulf Stream...

...and of course there's a problem with looking at Walker's black subject. This looking is rather trecherous and loaded. Roberta Smith writes in her review of

After The Deluge:

"That she (Walker) is an African-American woman seems to be the last thing on her mind: one of her central messages is that slavery visited degradation equally on all concerned and that its tragic legacy poisons life for all Americans."

This is bullshit--a classy sidestep when you just want to get your 1000 words in without any fuss. Walker is representing a specific black subject that is writhing and seething and spilling, caught between the existential burden of being human and all the other burdens of being 5/8 of a person. A book detailing the survivors of the Amistad is chilling and gorgeous. Take the time to get as close to the vitrine as possible, to see the considered, distinguishing detail in each silhouette profile of each individual. Read the completely un-ironic descriptions of who these people are, what their parents do and where they came from. What they were doing right before they were sold into slavery. Compare the bizzare excess of Walker's hyperstylized black subject in her 2001 series

American Primitives to the Amistad book's sensitivity. To Edouart's reliance on conventions of whiteness and gentility, like very tiny feet.

Descent Into Hell, in the style of Hieronymous Bosch, is not representing whiteness here, nor is Joshua Shaw's

Deluge Towards Its Close. Edouart's capturing of whiteness is here to bounce off of what Walker is doing to similarly conventionalize and exaggerate blackness. This is not about unity, and to miss this is to sidestep the meat of this exhibit. Because what I can really sink my teeth into is how Walker's choices so deftly point, again and again, to that inside/outside problem. To this specific and hideous past that fills the black subject and spills out of it. This gesture--not water, not specifically Katrina but the way the levees were not high enough---predominates. This is not a show about water, it is about what water does and describes. It is about the pressure of being defined by an atrocity that is no longer happening but that we can't stop thinking about. That

is a very specific kind of flood, and that flood moves through the body and fills the space we share.

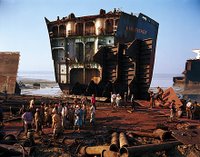

Walker is so good at representing this particular social landscape in which the past flows into the present, and it is a landscape that I am intimate with. I work with a crew of manual laborers that is exclusively slave-descended African American. I have no choice but to navigate this constant need for my colleagues to see things in terms of slavery, and it makes everything so tricky. I have worked hard with them for the better part of a year, and most of them are still not my friends, despite my best efforts. Most of them do not trust me because they keep thinking I have power over them, even though I am their colleague, not their boss. We wind up doing a high-stakes dance, in which they keep giving me power I don't have and then resenting me for it. And I keep failing to resist their power-shove and not understanding what the problem is. Really dumb stuff, like whether I am wearing a baseball cap or my wide-brimmed "overseer" hat, can make all the difference in the world. These guys are not stupid--the situation is just that visual and deeply coded. And try avoiding references to slavery when you actually are slaving, when you are breaking rocks in the hot sun! Conversations, especially requests, grow thick underbellies of subtext. And because I am no good at subtext, I get it wrong all the time.

Walker is interested in the "story of Muck." And my work life

is muck, a very specific muck that Walker mines and perverts and throws back at the (mostly white) viewer. And this, because the muck is so visual and because it is so difficult to talk about, could be the single most revolutionary thing any person dealing in race ever did. It could blow a hole in the wall of polite, ineffective silence that dooms day-to-day interactions between white and black people, that drives racism underground where it becomes a million little sulfurous hotsprings of mutual contempt. And since I happen to love my job and hate this one tiny part of it, I really want this work Walker is doing to be meaningful. I want it to be as powerful as Walker is.

But it's not. It's just not. I don't think I am asking too much. I don't want Walker to become the Unity Fairy, or even the lady at the Helpful Advice for White People About Blackness booth. She couldn't cure racism for me, and shouldn't even if she could. Art is not about that. All I want her to do is follow through on what she starts. I know this is a tall order. I know that I am not calling anyone out at work because I would rather just wear the wide-brimmed hat.

But you know, I tromp around a park trying desperately to get along with a handful of big black men from Astoria Houses. I do not have a show at the Met--a show that forcefully portrays the black body in turmoil and seething with rage. And I am not the one openly calling the viewer Massa and in all caps shouting CROUCH DOWN IN THE NIGGER TRENCHES! calling out to the black middle class for a race riot with one breath and politely suggesting that there is possibility for rebirth with the next. Kara Walker is too powerful to get away with this racist doubletalk. I do not buy her worn out conceit that she is the Met's House Negress and that playing out the dynamic she represents--soothing Massa with one hand while the other hand is a clenched fist that then explodes somewhere else, somewhere safe--is part of the concept.

I have no problem with her rage. It's the fact that she refuses to own the rage--to use it to step outside this hurtful system of pandering and resentment that turns me off.

After The Deluge is comparatively strong because much of the soothing happens in the wall text, leaving the gallery a strongly angry and devastated place. This relative directness gives her power that I didn't think she had. She has the power to turn the Nkisi nail-fetish figure into a portrait of a black body in turmoil, negating the figure's original purpose as a magical transformer. She has the power to make an inferred black subject loom over

The Deluge Towards Its Close. And she is strong enough to put herself and her own hand at the center of this madness, all nappy hair and pointed shark teeth and huge feet and billowing smoke that for once is not just a paper shape. Her

Text Cards, which I have previously found tedious because I hate being called a Massa, cement this show, make it abundantly clear that her subject is rage. So what is with all the sidestepping in the essay on the wall? Why move away from the horrific and racialized particulars of Katrina to focus on more polite topics like water in general? Why claim that this show has any content about renewal or rebirth?

The only really powerful thing art does is create distance and new perspectives on what we see every day. Walker halts this process halfway. She undoes this revolutionary act of looking by

doing exactly what she

sees. Her wall-text works too hard to make me feel okay about what I am looking at. And Walker's reliance on the Met's collection winds up functioning as just another code in which to speak. All that art history puts viewers (and reviewers) at a disadvantage. Is the correct reading what it all looks like or what I learned in school? Or, in the case of Copley's

Watson and the Shark or Homer's

The Gulf Stream, is the correct reading based on newer afrocentric texts that I haven't read? For every single ounce of power Walker displays openly in

After The Deluge, she counters with a dose of backpedaling or obfuscating detail. Every image culled from the Met's collection is so rich. The dense salon-style hanging and sheer breadth functioned in the moment as a shock-and-awe tactic. It heightened my visceral response to the show to be confronted with

all this work--a big, slow-moving, well telegraphed punch in the eyes. But as the time comes to really sit down and think about what Walker is doing, each image becomes its own little rabbit hole down which I am constantly slipping and losing the real question:

What is Walker doing when she is not hiding behind these images and histories?I want Walker to stop diluting this rage. I want her to just fucking say what's on her mind. I want to be able to trust and believe her. I do buy that the rage I saw at the Met--the rage that I don't think I am supposed to actually talk about because it is so shifty and encoded--is completely real, and that it is rooted in this twisted, uniquely visual legacy of slavery. I absolutely buy that there are demons and skeletons and people fucking and sucking and beating and burning locked inside Walker's black subject. And I want to see it. I don't want to see all of this pain and rage because it's exotic, or to make me feel better about my whiteness. I want to see it because in my life all that rage is a huge boil that needs desperately to be lanced, and I have no power to lance it. I buy that Walker is angry, and that she has a gift, and that this gift is being able to hold her anger far enough away from her so that she can play with it, twist and sculpt it.

What does one do with such a scary gift? What if Walker just put together

After the Deluge and let it sit there, writhing and slithering and lashing and fist-pumping? What if she did no apologizing on the wall text whatsoever, and left us at crouching down in the nigger trenches? With her own naked words? What if we had to interpret these images ourselves, visually, without relying on wall-texts and art history to save us from the rage Walker wants so desperately to represent?

Well, then she would be making a definitive statement of what is actually going on. And if she did that, I could, as a reviewer, turn it into a dialogue. I could say something with integrity. I could say, "I had no idea what all this pain feels like until you showed me." or "We are more alike than you think" or "I'm not your Massa and resent being forced into this position as much as you resent always winding up a Slave."

As

After the Deluge stands, covering up its rage in layers of historical detail and bracketed by downcast eyes saying that the unifying element is water, which it is not, and that the water is cleansing, which it is not, it is still falling flat, merely a monologue about the Great Historical Wrong that will never be overcome, that we can never move past because we can never admit that it is truly there.