You seem to be talking about sculpture in which the materials physicality is either the point or transcended to point to narrative, but I think this is a really narrow axis. Deb and I were talking about a different axis that might yield some interesting ideas to explore.

I'm just going to restate your post in case I misunderstood it. At one end you're talking about David, which is basically narrative, illusionistic art, the same tradition that birthed Western painting

and at the other end is modernist sculpture, with a heavy Greenburg influence:

and at the other end is modernist sculpture, with a heavy Greenburg influence:

To me, this is the reductive axis of modernism, that you take the old, narrative tradition of Europe, in which the medium was primarily a means to creating the illusion, and then flipping and redefining that tradition so that the theoretical "essence" of the dicipline as defined by its media becomes the focus. In Greenburg's terms that was pigment on a flat surface for painting, and possibly material in space for sculpture. What interested me about Deb's work situation is that she's alongside a lot of guys from the modernist, essentiallist tradition, but the artists in the current show don't actually work with that set of values. The ones who are more representational have a readymade framework that we can all understand their work through, but the folks working more in the "ready made" tradition of Duchamp, say, are getting pressed into a framework (modernism) that isn't really applicable.

The axis I was talking with Deb about has material culture on one end (modernism with it's focus on the essential qualities of being material in space) and object creation in which the objects as ready mades are essential to the way the object is art.

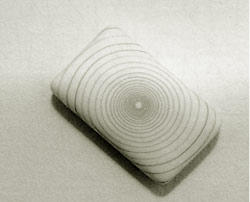

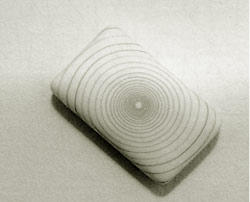

Tom Friedman's soap is a good example of what I'm thinking of. It's not great formal sculpture. Cast it in bronze and it's a doorstop. What makes it is that it is soap and human hair.

Out of the three of us, I would say that only Deb works in the first axis. I think you work closer to the material end of the second axis and I work closer to the ready made end.

But this is a first thought outloud.

I'm just going to restate your post in case I misunderstood it. At one end you're talking about David, which is basically narrative, illusionistic art, the same tradition that birthed Western painting

and at the other end is modernist sculpture, with a heavy Greenburg influence:

and at the other end is modernist sculpture, with a heavy Greenburg influence:

To me, this is the reductive axis of modernism, that you take the old, narrative tradition of Europe, in which the medium was primarily a means to creating the illusion, and then flipping and redefining that tradition so that the theoretical "essence" of the dicipline as defined by its media becomes the focus. In Greenburg's terms that was pigment on a flat surface for painting, and possibly material in space for sculpture. What interested me about Deb's work situation is that she's alongside a lot of guys from the modernist, essentiallist tradition, but the artists in the current show don't actually work with that set of values. The ones who are more representational have a readymade framework that we can all understand their work through, but the folks working more in the "ready made" tradition of Duchamp, say, are getting pressed into a framework (modernism) that isn't really applicable.

The axis I was talking with Deb about has material culture on one end (modernism with it's focus on the essential qualities of being material in space) and object creation in which the objects as ready mades are essential to the way the object is art.

Tom Friedman's soap is a good example of what I'm thinking of. It's not great formal sculpture. Cast it in bronze and it's a doorstop. What makes it is that it is soap and human hair.

Out of the three of us, I would say that only Deb works in the first axis. I think you work closer to the material end of the second axis and I work closer to the ready made end.

But this is a first thought outloud.

2 Comments:

Yeah, I think I would define the axis like this:

On one hand, you have folks who are working with *material* and harnessing formal elements in order to arrive at an abstraction.

This abstraction does not need to be absolute or deny representation. Charles Ray and Jennifer Pastor consistently abstract representations of real things (how do we get a picture of Unpainted Sculpture on the blog?).

The whole point of Unpainted Sculpture is that it's *not* a car anymore.

On the other hand, there are folks who are using and arranging materials and things that do not work toward an abstraction. I would agree with you, Kat, that in this group splits into Material Innovators (Friedman, Joel) and Assemblage.

Material innovators like Friedman are depending on the fact of the material and are not harnessing it in the service of an abstraction.

Assemblage dispenses entirely with the concept of material. It requires that the things themselves keep their identity. Eleanor Antin's portraits of women are a great example of this. In order for them to be meaningful, you have to read the baggage of the objects juxtaposed against one another. You use the same logic that you use to "read" a person in the grocery line based on what's in their cart.

To contrast, the satisfying (if often thin) punchline of Friedman's work is "Oh, my! That's soap and a hair!" (or bubblegum, or whatever.)

I think that these three distinct approaches to working in three dimensions have been jumbled together for so long that it's difficult to develop a useful language for dealing with sculpture.

I think it might be interesting to think about any individual sculpture as having positions on these two axes (is that how you pluralize axis?):

Abstraction v. Literalism

Material v. Object

Which basically puts us back 40+ years to Michael Fried v. Donald Judd.

yes, axes is the right plural of axis. i looked it up on dictionary.com. i think you can only put a picture in a post, not in a comment.

i like your refinement. i may have to make a graph of that, in my spare time.

Post a Comment

<< Home